Just Distribution in Debt Deliberation (Experiment)

Project Stream 7 · Sven Hoeppner

How Do We Share Losses Fairly? When a company goes bankrupt, there’s often not enough money left to pay everyone what they are owed. This creates a difficult problem: how should the remaining assets be divided among the creditors? While the common solution is to pay everyone a share proportional to their original claim, this is not the only way to approach the problem. Other methods, some with roots in ancient philosophy and religious texts, offer different ideas of what is fair. For example, one rule might try to give everyone an equal amount, while another might focus on making sure everyone shares the loss equally.

To understand what people consider a fair way to handle such situations, we conducted a laboratory experiment. We presented participants with four different rules for dividing assets in a simulated bankruptcy.First, we asked participants to decide how much they would be willing to pay for each rule to be used, but without knowing what their own financial stake in the outcome would be. In this situation, as if behind a “veil of ignorance,” people had to consider the fairness of the rules from an impartial perspective.

As for the results we found that while the commonly used proportionality rule was popular, a rule that aims to give everyone equal awards was valued just as highly. A rule that focuses on equalizing the losses was the least popular. However, things changed dramatically when we lifted the veil and told participants their specific position – whether they had a small, medium, or large claim. People’s preferences quickly shifted to favor the rule that would benefit their own situation the most. Those with small claims were now strongly in favor of the equal awards rule, while those with large claims preferred the rule that would minimize their individual losses. This demonstrates a strong self-serving bias. These findings highlight a crucial tension: the rules we might agree on as fair from an impartial standpoint are not always the ones we prefer when our own interests are on the line. This has important implications for how we design and regulate systems for handling everything from corporate bankruptcy to the division of public resources.

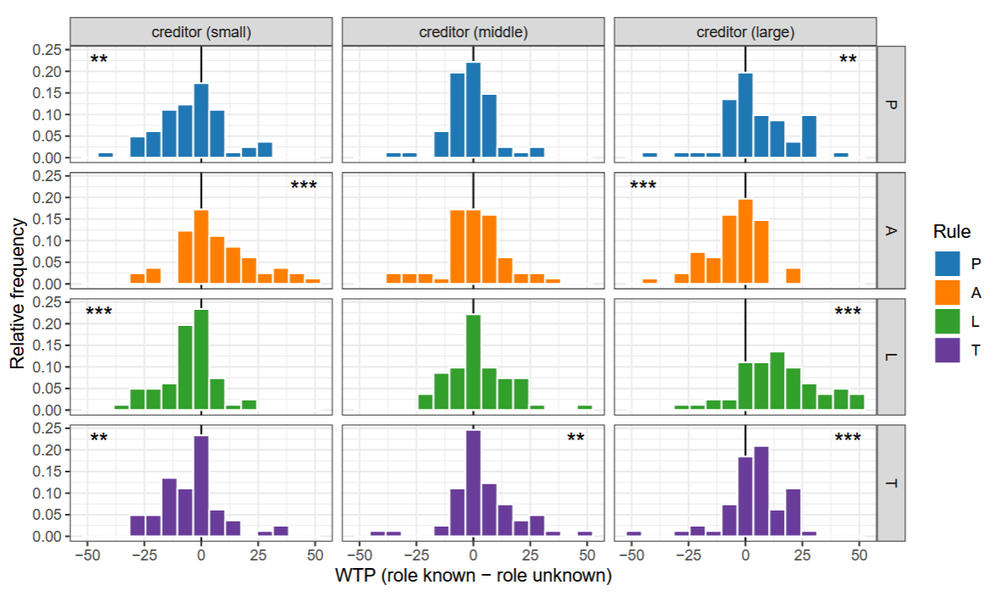

This figure visualizes how learning their personal stake in the outcome changed participants' preferences for the different distribution rules. Each panel shows the change in participants' willingness-to-pay (WTP) after they were informed of their role as a small, middle, or large creditor. A distribution shifted to the right of the central line (positive values) means that participants valued that rule more once they knew their role. A distribution shifted to the left (negative values) means they valued that rule less.

The chart clearly reveals a pattern of self-interest. Small creditors (left column), for example, significantly increased their preference for the 'Constrained Equal Awards' rule (A), which benefits them, while their preference for the other rules decreased. In contrast, large creditors (right column) began to strongly favor the 'Constrained Equal Losses' rule (L) and the Talmud rule (T), while their liking for the 'Constrained Equal Awards' rule (A) dropped significantly. The asterisks indicate that these shifts are statistically significant and not just a result of chance.

Explanatory Note – Distribution Rules

The Proportionality Rule (P): This is the most common approach used in corporate insolvency proceedings. It divides the remaining assets in proportion to the size of each creditor's pre-insolvency claim. In simple terms, if a creditor was owed 30% of the total debt, they receive 30% of the money that is left. This principle is inspired by Aristotle.

The Constrained Equal Awards Rule (A): This rule takes a different approach by dividing the available money equally among all claimants, with one important caveat: no one can receive more than their original claim. For example, if there are three creditors and enough money for each to get $50, but one creditor was only owed $40, that creditor would get their $40, and the remaining funds would be divided among the others. This concept is linked to the medieval philosopher Moses Maimonides.

The Constrained Equal Losses Rule (L): Instead of equally dividing what is left, this rule focuses on ensuring everyone experiences an equal amount of loss. It calculates the total shortfall (the sum of all claims minus the available funds) and divides this loss equally among claimants. The process is constrained so that no claimant can lose more than their original claim, which means their payout cannot go below zero. This rule also has its roots in the philosophy of Maimonides.

The Talmud Rule (T): This rule is an extension of the "Contested Garment Rule" found in the Talmud. It functions as a hybrid, combining the principles of the Equal Awards and Equal Losses rules. Its behavior changes depending on the size of the remaining assets compared to the total claims. If the available funds are less than half of the total claims, it functions like the Constrained Equal Awards (A) rule. If the funds exceed half of the total claims, it behaves like the Constrained Equal Losses (L) rule to distribute the amount above the halfway point.

Project Funding

Funded by the European Union (ERC, RESOLVENCY, No. 950427). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.